By the time Dr. Constance Smith Hendricks introduces herself as “a nurse of 52 years,” you can already hear the longer story underneath it.

Because her career is not just long. It is infrastructural.

Dr. Hendricks has spent decades building the quiet systems that make nursing possible. She has created programs from scratch, led schools through moments of change, expanded access to health information across Alabama, and preserved the stories of nurses whose impact might otherwise have disappeared into the background of history.

Nurse Approved connected with Dr. Hendricks through the Alabama Nurses Foundation, as part of our Black History Month series: The Unseen Shifts, How Nurses of Color Have Quietly Changed Healthcare Systems. What we found was a life’s work defined by persistence, vision, and a deep belief that communities deserve access, not just admiration.

A Nursing Start Shaped By History, and By a Hard Choice

Dr. Hendricks graduated from the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Nursing (UABSON) in 1974, entering the profession at a time when opportunity was still being rationed by race in ways both direct and “policy-shaped.”

She was raised in Selma, Alabama. Her father was a 100 percent disabled veteran, and her mother was a school teacher. Her ability to attend college depended on her father’s VA education benefits.

Dr. Hendricks had been admitted to Tuskegee University, the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), and Grady Memorial Hospital’s nursing program in Atlanta. She had dreamed of becoming a Tuskegee nurse and describes it as “being a Tuskegee nurse was like the cat’s meow.” But she learned that if she chose Tuskegee, she would not receive VA support.

So she went where the funding would follow, even though it was not her first choice.

It became a pattern: she learned early how systems work, who they serve, and what it takes to move through them without losing yourself.

The Barrier She Broke Before She Even Knew It Was a Barrier

As a freshman at UAB, Dr. Hendricks attended a rush event where the invitation said “everybody.” She took it at face value. She went.

She and another African American student became the first two to integrate the Alpha Sigma Tau sorority at UAB in the spring of 1972. By the time she graduated, she had become the chapter’s president.

Later in 1974, when she married shortly after graduation, her white sorority sisters stood with her as part of her bridal party. In Selma, she says, it was one of the city’s first integrated weddings and people still talk about it 50 years later.

She describes these moments plainly. Not as triumph speeches. As facts. As evidence of what happens when you walk through doors that were not designed with you in mind, and refuse to shrink once you are inside.

The Unseen Shift: Community Care Before It Had a Name

Dr. Hendricks began her clinical career at University Hospital as a NICU nurse, but she quickly moved into teaching because she wanted to work in the community and get out of the night shift as a new bride.

Then, in 1975–1976, she did something that would later become a national model, without realizing she was ahead of the curve.

She operated a nurse-managed clinic in an inner-city Birmingham housing project, supervising nursing students who provided care in collaboration with the health department. They provided routine health services in community health training, including pap smears and protocol-based follow-ups, at a time when nurse practitioner roles were not yet widely established as we understand them today.

She opened a second nurse-managed clinic in another housing project. Residents, she recalls, were protective of the students and faculty because care was being delivered with respect, inside their homes and alongside their needs.

Only later did she hear the term “nurse-managed clinic” and realize, “We were doing that back in ’75.”

That is the unseen shift in one sentence: nursing practice that changes systems often looks ordinary while it is happening.

Education as Access: Building Nurses, Building Programs

Over the decades, Dr. Hendricks became not just an educator but a builder of nursing education itself.

She describes her path as an “evolving ladder,” shaped by opportunity, resistance, and the decision to keep moving forward anyway.

Among her roles and accomplishments:

• She served as Dean of the Hampton University School of Nursing.

• She served as Dean of Nursing at Tuskegee University, returning to lead a program with deep historical roots in Alabama.

• She became the Founding Dean of Nursing at Concordia College Alabama in Selma, creating an RN-to-BSN program that achieved national accreditation and graduated two cohorts before the college announced its closure.

• She later developed the nursing program at the University of Montevallo, writing it “from the first word” and shepherding it through the approval process with the Alabama Board of Nursing, helping select the dean, and then stepping back intentionally so she would not become “the weak link” as the program grew. The program is expected to graduate its first two students in May 2026.

She has also been a Professor Emerita at Auburn University School of Nursing since 2015, after completing the five-year Charles W. Barkley Endowed Professor Chair, where she was one of the inaugural awardees.

Her impact is visible in syllabi, accreditation documents, faculty pipelines, and student outcomes. But it is also visible in the quieter places: a nurse who can now become a nurse because a program exists where it did not before.

“Taking IT to the People Southern Style”

If Dr. Hendricks has a signature phrase, it may be this one.

She established e-health information stations in more than 50 sites across Alabama, a model she describes as “Taking IT to the People Southern Style.” The stations provide access to evidence-based health information and self-care strategies that are updated every two months. She estimates that more than 800 people per month access the information.

The idea is simple and radical: people cannot make informed health decisions if the information never reaches them in a usable form.

Her approach came from years of community-based work that began long before digital screens were mounted on walls. She remembers creating health education posters and posting them in places people actually go: beauty shops, barber shops, and churches.

You take information to the people. You make it plain. You make it recognizable. You translate science into language that respects real life.

She describes the initiative as translational research, breaking complex health information down so people can understand it. “There’s no guarantee,” she says, “but at least it won’t be because they didn’t have access to information.”

Preserving Nursing History When the World Shut Down

During the COVID-19 lockdown, Dr. Hendricks helped create what became a record of Alabama nursing impact: a project that began as a “great reveal” webinar and grew into a book when the team realized the stories were too important to discard.

The result was a book, Alabama Notable Nurses, which profiles more than 250 Alabama RNs who made a difference. She describes carrying her copy to events and asking featured nurses to sign their pages, collecting living signatures to go alongside the written record.

For Dr. Hendricks, this was not nostalgia. It was nursing ethics.

“In nursing, we’ve been taught: if it’s not written, it wasn’t done,” she says.

She also recognized a painful gap in her teaching of associate degree nursing students.

Many had never learned nursing history beyond Florence Nightingale. In response, she created a presentation she calls “Florence and the Two Marys,” spotlighting two of the most influential Black nurses in history, Mary Seacole and Mary Mahoney. She then went a step further, designing assignments that required students to interview nurses in their own communities, connecting history to lived experience and ensuring those stories would not be overlooked again.

History, in her view, is not extra. It is professional grounding. And without it, nurses are too easily erased.

What It Cost, and What She Learned About Timing

Dr. Hendricks does not romanticize the road.

She speaks candidly about the prejudice she encountered as a Black woman and as a single mother. She describes being questioned, underestimated, and forced to prove herself in rooms where she should have been evaluated solely on her work.

When she was at Boston College earning her PhD, she recalls being told she “talked funny,” and a faculty member asked whether “she knew English” was taught at Auburn University. She describes how assumptions followed her into her daughter’s school life, too, until she put on her suit and showed up in person, letting people see the reality they had refused to imagine.

But some of her most powerful guidance is about strategy.

“Learn the rules,” she says. “You can’t make a change unless you’re at the table.”

She encourages nurses to know the criteria, meet them, and work within them.

“Pick your battles,” she says. “Timing is everything. Sometimes you don’t fight right then. But it doesn’t mean you don’t fight.”

Still Building, Still Honoring

Even in retirement, Dr. Hendricks continues to create structures that outlast a single career.

At the time of this interview, she was organizing a Nurse Honor Guard chapter in Selma and Dallas County, continuing her belief that how we honor nurses matters, too. Recognition is not just celebratory. It is historical. It tells the next generation that this work is worthy of memory.

And then she offers an invitation that feels like a benediction.

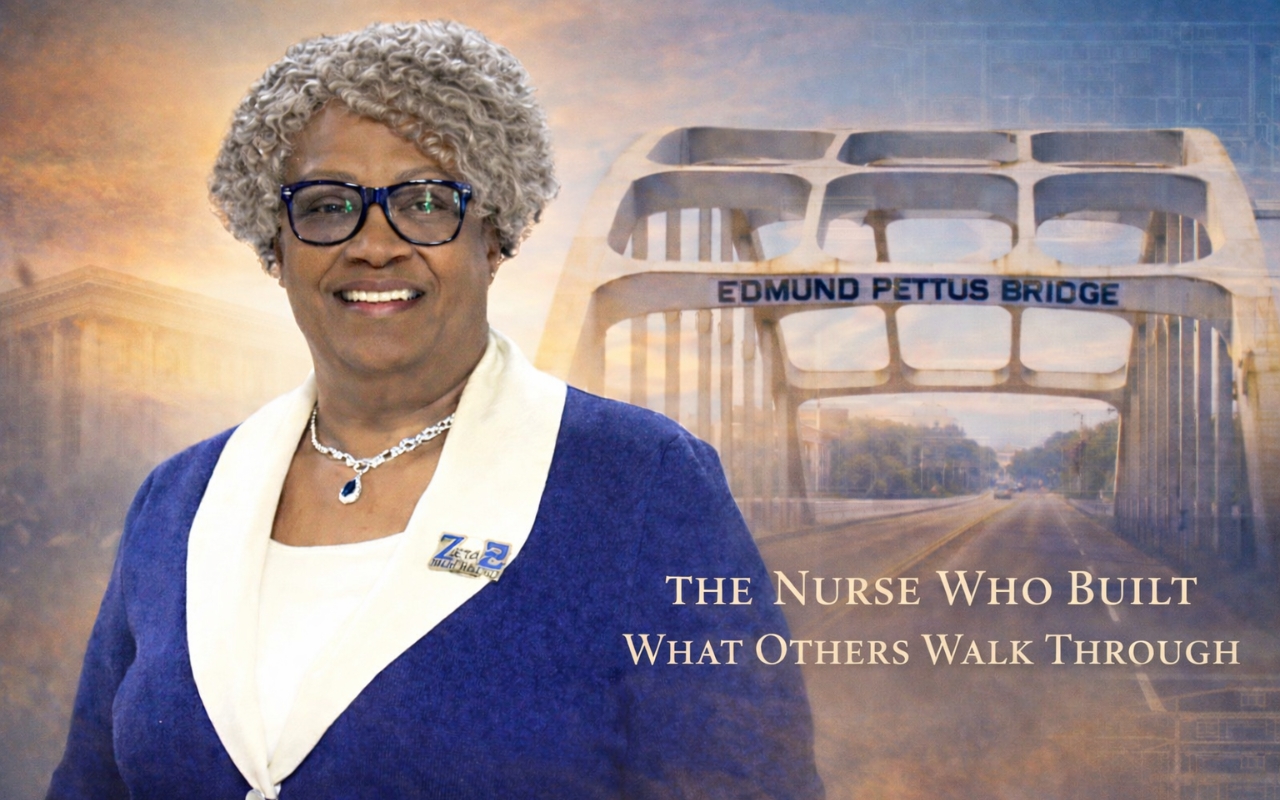

Talking to her while she was in historic Selma, the place she was born, she says she will walk across the Edmund Pettus Bridge with you anytime you come. If you have not had that lived experience, she believes you should not go through life without it.

It is not a tourist line. It is a reminder. Place matters. History matters. And systems do not shift without people willing to carry them, challenge them, and rebuild them.

Why Dr. Hendricks Belongs in Black History Month, and in Nursing History

Dr. Constance Smith Hendricks did not just advance in nursing.

She expanded what nursing could reach.

She built programs to help students become nurses.

She built access points so communities could get health information.

She built records so nurses would not vanish from history.

And she built pathways through systems that were never designed to be welcoming, without losing her commitment to bringing others with her.

Her career is proof that the “unseen shifts” are real.

They live in the infrastructure.

Her career was infrastructural.

And infrastructure, once built, carries generations.